Life moves at a meandering sort of pace out here on the western cusp of the United Kingdom, leaning on the Here Be Dragons signs and wondering what unseasonable weather events the glories of climate change will bring us next. So when I realised that our eldest son, Gawain and his fiancée Sue would be in Ennis on Thursday evening for a pre-tournament simul, I was struck by something of an inspiration. I should probably explain a couple of things first of all.

Life moves at a meandering sort of pace out here on the western cusp of the United Kingdom, leaning on the Here Be Dragons signs and wondering what unseasonable weather events the glories of climate change will bring us next. So when I realised that our eldest son, Gawain and his fiancée Sue would be in Ennis on Thursday evening for a pre-tournament simul, I was struck by something of an inspiration. I should probably explain a couple of things first of all.

A ‘simul’ is a chess-players’ abbreviation for a simultaneous demonstration, one of those exhibitions in which an expert player takes on a roomful of opponents at the same time, strolling from board to board and trusting that his (or her, occasionally) instinct and experience will outweigh the numerical odds. As a grandmaster and professional chess player, Gawain does quite a lot of these, and since Ennis is, as he puts it, ‘one of his home towns’, his adolescence having coincided with a particularly nomadic tendency on our part, he was happy to combine the event with a degree of social reunion. And since the simul was being held in a pub, the two birds were very neatly stoned.

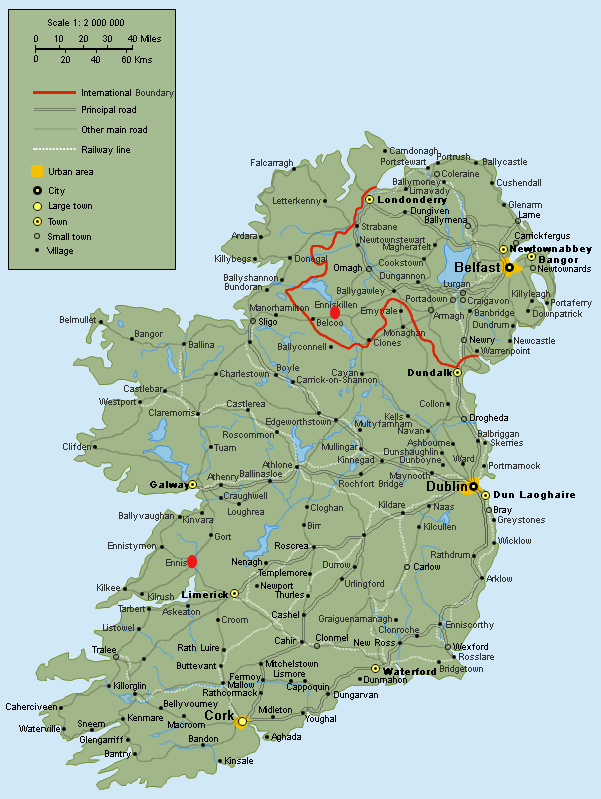

The second thing to explain is that, despite the passing similarity of their names, Ennis and Enniskillen are, in Irish terms, a very long way away from one another. This is not another Ballymena-Ballymoney tale. Ennis, or Inis, is simply the Irish for ‘island’, Enniskillen being, more or less, an island in the middle of Lough Erne, while Ennis, in its Franciscan infancy, was surrounded by the River Fergus. According to the road atlas, Ennis and Enniskillen are 153 miles apart, or 245 kilometres (Northern Ireland uses one and the Republic the other) as marked on the map here with tasteful red blobs. Owing to the paradoxical nature of County Donegal, Northern Ireland is not always north of the South, but in this case it is, the top blob being Enniskillen and the bottom one Ennis.

The second thing to explain is that, despite the passing similarity of their names, Ennis and Enniskillen are, in Irish terms, a very long way away from one another. This is not another Ballymena-Ballymoney tale. Ennis, or Inis, is simply the Irish for ‘island’, Enniskillen being, more or less, an island in the middle of Lough Erne, while Ennis, in its Franciscan infancy, was surrounded by the River Fergus. According to the road atlas, Ennis and Enniskillen are 153 miles apart, or 245 kilometres (Northern Ireland uses one and the Republic the other) as marked on the map here with tasteful red blobs. Owing to the paradoxical nature of County Donegal, Northern Ireland is not always north of the South, but in this case it is, the top blob being Enniskillen and the bottom one Ennis.

150-odd (and sometimes, as you’ll see, very odd) miles doesn’t sound much, but as another glance at the map will suggest, despite the Celtic Tiger, peace dividend and frankly scary facility in winning Eurovision, the west of Ireland is still, thanks be to her holy saints, fundamentally a mid-1950s rural backwater. Neither Ennis nor Enniskillen, according to the map legend (that’s a nice etymological oddity in itself) is even a Town, and only Cork in the entire left-hand half of the island counts as a Large Town. So it wasn’t a great surprise when, checking the Journey Planner on the Bus Eireann website, I found that it would take nearly seven hours to travel from one to the other by bus. Fourteen hours return, on six buses, with a bit of hanging about in the middle. Or, as I preferred to think of it, only fourteen hours. After all, seeing Gawain and Sue, who are currently based in London, usually involves a minimum, each way, of a bus, a taxi, another bus, a ferry, another bus and several trains. And before that they were in New Zealand…

So I did what you’re supposed to do with inspiration, and by half-past eleven next morning was settling myself on the first bus, due westward from Enniskillen to Sligo. This humble little route passes through some of the most beautiful countryside I’ve ever seen (and I’m counting the Alps, Tuscany and the Scottish Highlands) and I wanted to be sure of enjoying it to the utmost. Accordingly, I selected a place on the left hand side of the bus, with a minimum of chewing gum stuck on to the seat back in front of me and a seat pre-reclined (I can never get the hang of adjusting them) for optimum comfort. The secret of successful bus travel is to make yourself as much at home as is compatible with the comfort of your fellow-passengers, so it’s kind, if the bus is fairly empty, to choose a seat neither immediately in front of nor behind anyone else, and if that’s not possible, to avoid twanging the elasticated net behind their seat, kicking the fold-down foot rest or playing your iPod at high volume through leaky earphones. We’re a tolerant lot, on the whole though, and if you insist on talking on your mobile phone, munching noisy crisps or slurping from suspicious cans (alcohol is forbidden on Irish buses), no one will make much of a fuss.

So I did what you’re supposed to do with inspiration, and by half-past eleven next morning was settling myself on the first bus, due westward from Enniskillen to Sligo. This humble little route passes through some of the most beautiful countryside I’ve ever seen (and I’m counting the Alps, Tuscany and the Scottish Highlands) and I wanted to be sure of enjoying it to the utmost. Accordingly, I selected a place on the left hand side of the bus, with a minimum of chewing gum stuck on to the seat back in front of me and a seat pre-reclined (I can never get the hang of adjusting them) for optimum comfort. The secret of successful bus travel is to make yourself as much at home as is compatible with the comfort of your fellow-passengers, so it’s kind, if the bus is fairly empty, to choose a seat neither immediately in front of nor behind anyone else, and if that’s not possible, to avoid twanging the elasticated net behind their seat, kicking the fold-down foot rest or playing your iPod at high volume through leaky earphones. We’re a tolerant lot, on the whole though, and if you insist on talking on your mobile phone, munching noisy crisps or slurping from suspicious cans (alcohol is forbidden on Irish buses), no one will make much of a fuss.

For one thing, there’s so much else to think about. I’m almost sure that Bus Eireann windows aren’t actually enchanted. It must just be something about being a bit higher up than usual, and having such a wide expanse of glass to look through, and not having to do anything but look (I had a book with me, but most of the Enniskillen-Sligo route is too bumpy for non-nauseous reading). Whatever it was, we’d only travelled a couple of hundred yards when the first vignette of quintessential Irish life manifested itself in the form of three men in a boat. Three men being neither Edwardian Londoners nor portly comedians but locals out for a morning’s fishing, and the boat being of the wooden rowing variety rather than the petrol-guzzling cruisers which generally dominate the lough. Over the next few miles we passed donkeys, an elderly couple grappling with a very small tractor, caramel-brown cows and meadows starred with wildflowers. We also, to be strictly accurate, passed quite a few half-built houses and wildly inappropriate apartment blocks, testaments to the property bubble that grew, and burst, on both sides of the border.

As we travelled westward, things, as is their wont, grew slightly more bizarre, not least as we reached the Rainbow Ballroom in Glenfarne. It turns out, according to Wikipedia, that the Ballroom is in fact quite famous, having hosted the great names of the showbands era and insprired a story by William Trevor which was subsequently filmed by the BBC. I’d never before seen it other than entirely deserted (Glenfarne has a population of three farmers and a elderly hen) but this time we were treated to the exhilarating experience of a real live Garda checkpoint. (This was the week of the Queen’s historic visit to Ireland and the discovery of a bomb on a bus from Kildare so Bus Eireann customers were clearly prime terrorism suspects.) A genial man in one of those shapeless cotton hats worn on 1970s camping trips ambled onto the bus and viewed the assembled passengers, by now consisting of a man in his seventies, a woman of around sixty and me. His interrogation was swift and merciless. “All right, folks?”

As we travelled westward, things, as is their wont, grew slightly more bizarre, not least as we reached the Rainbow Ballroom in Glenfarne. It turns out, according to Wikipedia, that the Ballroom is in fact quite famous, having hosted the great names of the showbands era and insprired a story by William Trevor which was subsequently filmed by the BBC. I’d never before seen it other than entirely deserted (Glenfarne has a population of three farmers and a elderly hen) but this time we were treated to the exhilarating experience of a real live Garda checkpoint. (This was the week of the Queen’s historic visit to Ireland and the discovery of a bomb on a bus from Kildare so Bus Eireann customers were clearly prime terrorism suspects.) A genial man in one of those shapeless cotton hats worn on 1970s camping trips ambled onto the bus and viewed the assembled passengers, by now consisting of a man in his seventies, a woman of around sixty and me. His interrogation was swift and merciless. “All right, folks?”

We crumbled under the pressure, nodding shamelessly. At least one of us even smiled. The Fenians must have gyrated in their graves.

Approaching Sligo, the landscape changed, grew starker and more dramatic as we passed by Glencar Lough, looking towards the Dartry Mountains. There’s nothing to do here but gasp at the wonder of it. Still, though, the little domestic details: a white cow paddling in a small stream.

Then, ahead, the first glimpse of the Atlantic, past the King’s Mountain to Drumcliff Bay.

In Sligo I had an hour between buses so dashed, in a sudden downpour, around a few charity shops, collecting books and, almost, a vibrant but sadly oversized green raincoat. There’s a café here where they make some of the best sandwiches in Ireland but I’d brought my own this time. Anyway, I couldn’t risk missing the next bus, south down to Galway. There’s always a tiny batsqueak of excitement about Sligo bus station; there’s surfing at Strandhill and sometimes the cosmopolitan whiff of an Australian accent. The next bus was, in keeping, busier and slgihtly grander, with vinyl trim to the seats and, yes, an overweight man in a Star Wars T-shirt. We were in mainstream bus culture now. A long section of the journey, this one, and not nearly so photogenic, though smoother, so I could read – Peter Singer’s How Are We To Live? – I always seem to be reading Peter Singer around Sligo – last time it was his stunning The Life You Can Save – and only glance desultorily at the abandoned train track, sudden jubliation of lupins and the dreary 1950s religious theme park that is Knock and its crazy airport.

Galway bus station, cramped and chaotic, was busy at five o’clock but the final bus was close at hand. The driver inspected my ticket with amusement. “Enniskillen to Ennis? Bit long, like, isn’t it?” Galway has some new cycle lanes since I was here last, with provocative signs: Burn Fat Not Oil. Past the stretched-out suburbs with their giant roundabouts and greying hotels, we were back in rural Ireland, with rabbits, lambs and, this time, shire horses ankle deep in the streams. Through Gort,that quiet little town suddenly rejuvenated by its new Brazilian population and I was back in the Banner County, Daniel O’Connell’s County Clare. Not much had changed in the five years since we moved away, and the street map I’d brought in case of a sudden mindblank stayed unfolded.

I’d booked a bed at the Rowan Tree Hostel, which has just won Hostelworld’s Best Irish Hostel award (voted for by customers) for the second year running, and I could see why. It’s a fantastic place, perfectly located on the river at the edge of the town centre, with welcoming staff, bright, clean rooms, copious facilities and state-of-the-art security. I’d paid for the cheapest option, a place in a 14-bed dorm and was upgraded to a 10-bed, which I shared with only three, silent and considerate, fellow guests. I just had time to find my bunk (pre-allocated, avoiding awkwardness) dump the two bulging bags of books I’d bought in Sligo, have a quick wash and slip out again. The pub where the simul was being held was, by one of those coincidences by which we suspect that Providence smiles upon the slow traveller, only a few yards down the road, past the bridge from which we once, memorably, watched a family of baby otters, and the school where I taught English (TEFL variety) when we lived in Ennis.

I’d booked a bed at the Rowan Tree Hostel, which has just won Hostelworld’s Best Irish Hostel award (voted for by customers) for the second year running, and I could see why. It’s a fantastic place, perfectly located on the river at the edge of the town centre, with welcoming staff, bright, clean rooms, copious facilities and state-of-the-art security. I’d paid for the cheapest option, a place in a 14-bed dorm and was upgraded to a 10-bed, which I shared with only three, silent and considerate, fellow guests. I just had time to find my bunk (pre-allocated, avoiding awkwardness) dump the two bulging bags of books I’d bought in Sligo, have a quick wash and slip out again. The pub where the simul was being held was, by one of those coincidences by which we suspect that Providence smiles upon the slow traveller, only a few yards down the road, past the bridge from which we once, memorably, watched a family of baby otters, and the school where I taught English (TEFL variety) when we lived in Ennis.

The simul, in the comfortable surroundings of Tom Steele’s, more accustomed to the fiddle and flute than the fork and fianchetto, was a success, with the usual mix of local enthusiasts, wandering eccentrics and small boys with hovering mothers. It finished rather earlier than these things generally do, probably because there were, unusually, two grandmasters, Gawain and the excitingly named Vlad Jianu, making alternate moves. This made the whole thing more tricky, as they had not only to evaluate the position on each board they came to, but also to work out what, and why, their colleague had previously played. Despite their differing styles, however, they won every game and honour was thus satisfied.

The simul, in the comfortable surroundings of Tom Steele’s, more accustomed to the fiddle and flute than the fork and fianchetto, was a success, with the usual mix of local enthusiasts, wandering eccentrics and small boys with hovering mothers. It finished rather earlier than these things generally do, probably because there were, unusually, two grandmasters, Gawain and the excitingly named Vlad Jianu, making alternate moves. This made the whole thing more tricky, as they had not only to evaluate the position on each board they came to, but also to work out what, and why, their colleague had previously played. Despite their differing styles, however, they won every game and honour was thus satisfied.

Not quite so my hunger – I’d got the impression that either Tom Steele’s or its sister pub next door did food, and when this turned out not to be the case had to make do with a couple of pints. Sure, but isn’t Guinness a meal in itself? And seeing sixty-four pieces on the board was a good excuse for my incompetence at the chess variants we played until the early hours of the morning.

Not quite so my hunger – I’d got the impression that either Tom Steele’s or its sister pub next door did food, and when this turned out not to be the case had to make do with a couple of pints. Sure, but isn’t Guinness a meal in itself? And seeing sixty-four pieces on the board was a good excuse for my incompetence at the chess variants we played until the early hours of the morning.

A few, a very few, hours later I was briefly awoken, tucked up in the Rowan’s Tree’s excellent duvet, by a couple of quarrelling geese on the riverbank, not quite so silent or courteous as my room-mates. I slept again, though, getting up in time for the breakfast included in the hostel rate, simple but copious: coffee, orange juice, cereal and toast, the kind of food you actually want when not befuddled by fancy hotels with their kippers and pomegranate juice.

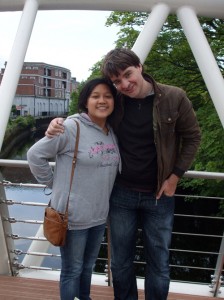

After breakfast I had a wander round Ennis in the sporadic rain (sporadic rain being pretty standard this far west), discovering that not much had changed in five years except for the closure/relocation of a few estate agents (presumably owing to the resounding property crash), construction of a pleasant pedestrian bridge (just visible behind the hostel in the last picture but two), closure of an electrical goods shop (see resounding p.c. above), opening of several small businesses with Brazilian, Central European and Afro-Caribbean themes (hurrah – showing where, and thanks to whom, any Irish recovery is likely to come) closure of the big toyshop (a possible decline in sacrament-related conspicuous consumption?) and, inevitably, a feckin’ Starbucks.

Thus updated, I met up with Gawain and Sue (here pictured on the aforementioned p.p. bridge) and we enjoyed a gentle stroll around the farmers’ market (bread, cheese, meat, jam, veg etc.)  and browse about the excellent Scéal Eile Books, also new since we left Ennis, and just about exactly what a second-hand bookshop ought to be.

and browse about the excellent Scéal Eile Books, also new since we left Ennis, and just about exactly what a second-hand bookshop ought to be.

Alas, the time passed with its customary alacrity, and by lunchtime I was back on the bus to Galway, leaving G & S to triumph in the Ennis Open tournament over the coming weekend. I finished the Singer, duly convinced that we ought to act ethically, though not necessarily for the reasons he gives, and moved onto lighter fare in the form of Rupert Christiansen’s admirable Complete Book of Aunts, certainly a Dahlia rather than an Agatha among books*. At Galway I deviated, as the chess players (quite innocently) put it, and instead of going up to Sligo took a cross-country bus that runs from Galway to Belfast on Fridays and Sundays only, presumably for the benefit of students. This was fairly crowded but pleasant enough, though the route, through Roscommon and Longford, showed Ireland rather at its most dismal, with boarded-up houses sprouting gardens of dock, sprawling suburbs of retail warehouses, a sad machinery auction and a half-shorn sheep in a front garden. Longford, incredibly, has a hairdressing salon called The Hair Trapp, which I’m sure is delightful, stylish and professional, but does seem to illustrate the fact, as yet undiscovered by Apprentice candidates, than not every pun is a good idea.

Deposited in the familiar surroundings of Cavan bus station, the last leg of the journey was on the Dublin-Donegal route, bringing me into Enniskillen in time for a glass of wine and plate of noodles with M at the Linen Hall. Where would we inpecunious travellers be without Wetherspoons? So,

The Moral of the Tale: Even in countries with pretty useless public transport systems like Ireland, even in the rural, underpopulated areas of those countries, even with little time at your disposal, it’s still possible to travel considerable distances reliably, cheaply (€42 euro return, and it would have been less if I’d not been coming back on a Friday) and enjoyably by bus. Viva Bus Eireann!

*Oh dear, don’t you? Wodehouse, Jeeves, Bertie’s aged relatives – what a treat you have in store.